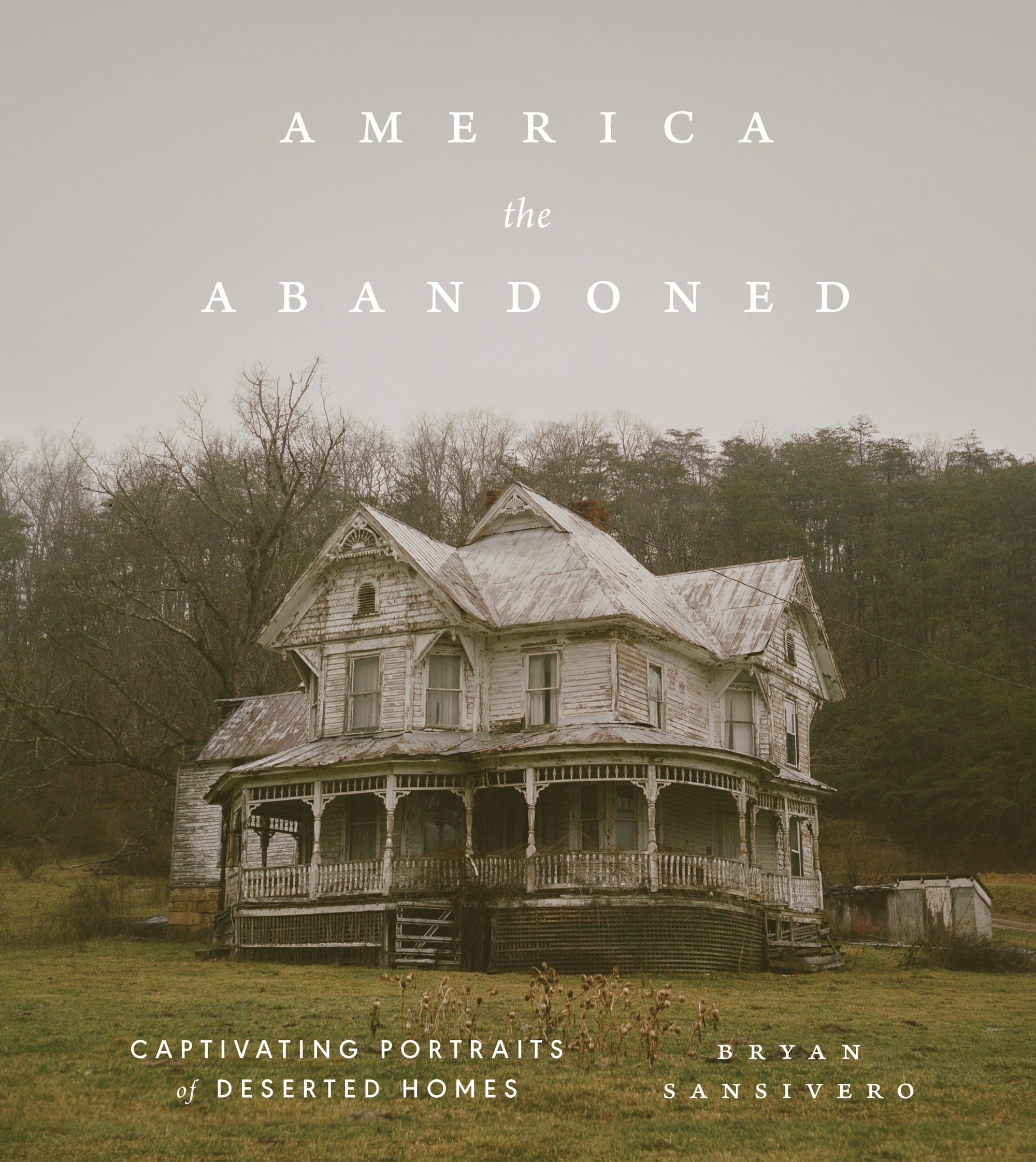

parametric batik patterns trace indonesian consulate building’s facade in jeddah, saudi arabia

Ibrahim Joharji designs Indonesian Consulate Building in Jeddah

The Indonesian Consulate Building in Jeddah by Ibrahim Joharji Architects contributes to the architectural landscape of diplomatic facilities in Saudi Arabia, where design carries both functional and symbolic roles. Diplomatic buildings are not only workplaces but also representations of national identity, requiring architecture to mediate between protocol, security, and cultural expression. The project is structured around a hierarchy of use, organizing spaces for diplomats, administrators, and staff through layered circulation systems. This spatial framework embeds distinctions of function and authority into the overall plan.

Navigating multiple regulatory frameworks, the design responds to the Saudi Building Code and incorporates references to Indonesia’s architectural heritage, which spans 28 recognized styles. Elements of the Rumah Gadang roofline were reinterpreted in a contemporary form, while triangular geometries derived from the peci, an Indonesian headpiece, were integrated as motifs of dignity and structure.

Indonesian Consulate in Jeddah by Ibrahim Joharji Architects | all images courtesy of Ibrahim Joharji Architects

Architecture as a framework for diplomacy and urban presence

The facade design combines cultural influences from both Indonesia and Saudi Arabia. Parametric patterns inspired by Indonesian Batik were interwoven with Islamic geometric references, producing a layered skin that operates as both shading and cultural signifier. Material choices were evaluated for their environmental impact. Reinforced concrete provides the necessary security measures, while facade systems, finishes, and mechanical components were selected to improve energy performance and reduce the building’s carbon footprint.

The Indonesian Consulate in Jeddah, by Ibrahim Joharji Architects Studio, illustrates how diplomatic architecture functions at the intersection of culture, regulation, and sustainability. By combining symbolic references with practical performance, the building establishes a framework where architecture supports diplomatic presence while contributing to the urban and environmental context.

a diplomatic building balancing function and cultural identity

triangular geometries inspired by the peci headpiece

facade patterns draw from Indonesian Batik traditions

islamic geometric references integrated into the skin

the facade operates as both cultural and climatic mediator

project info:

name: Indonesian Consulate Building – Jeddah

architects: Ibrahim Joharji Architects | @inj_architect

lead architect: Ibrahim Nawaf Joharji

client: Consulate General of the Republic of Indonesia – Jeddah

location: Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

built area: ~5,800 sqm

designboom has received this project from our DIY submissions feature, where we welcome our readers to submit their own work for publication. see more project submissions from our readers here.

edited by: christina vergopoulou | designboom

The post parametric batik patterns trace indonesian consulate building’s facade in jeddah, saudi arabia appeared first on designboom | architecture & design magazine.