‘Outcasts’ Highlights the Scientific Contributions of Trailblazing Artist and Naturalist Mary Banning

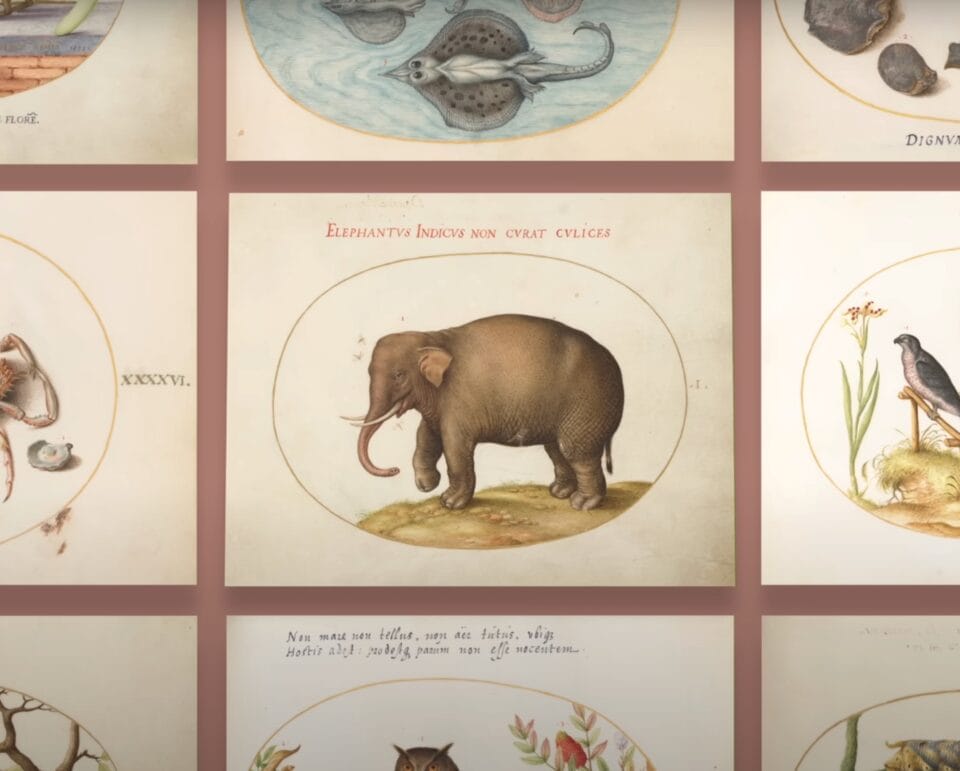

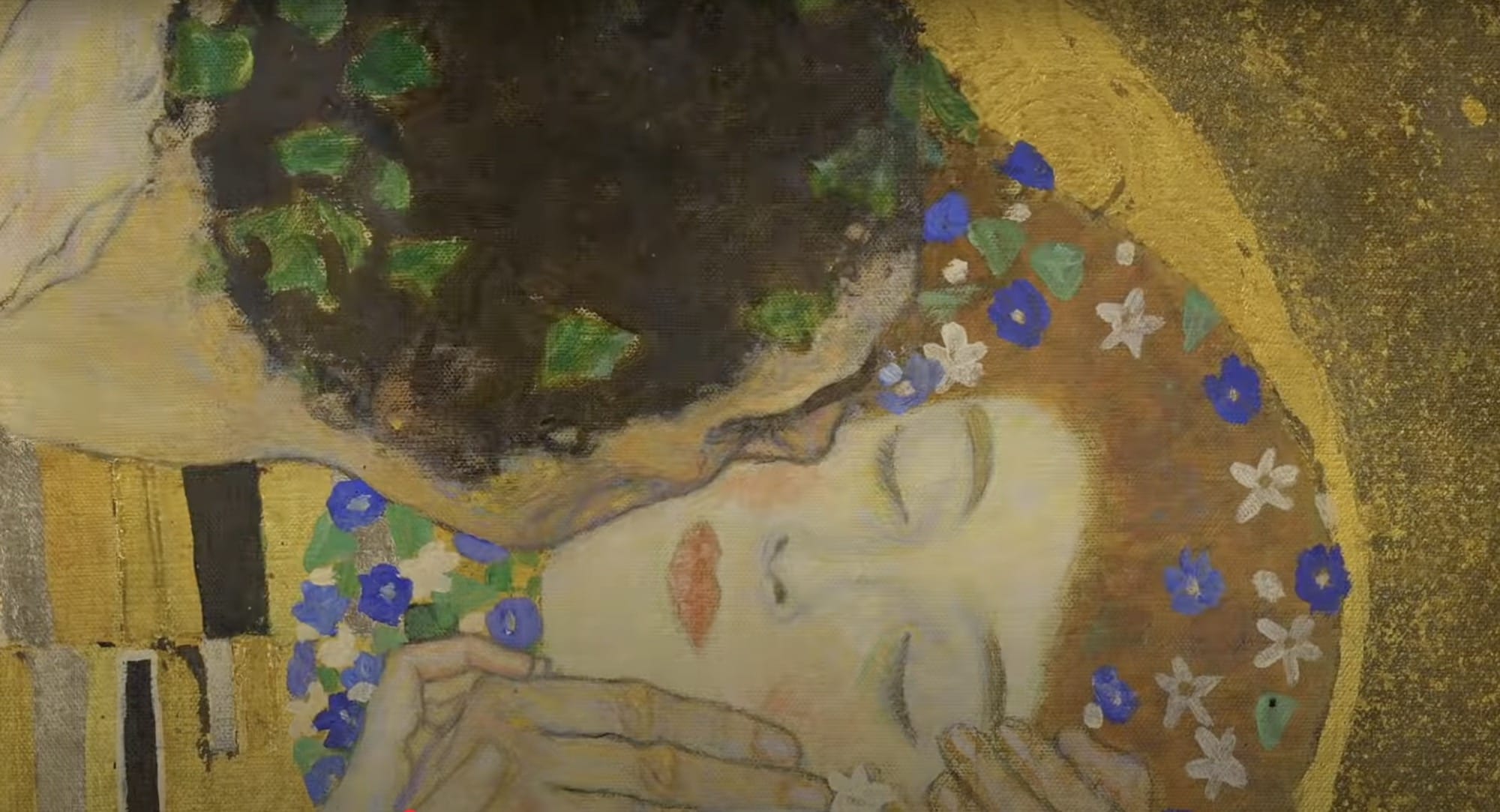

In the 1800s, mycology—the study of fungi—was a relatively new field, emerging around the same time as Enlightenment-era studies in botany and herbal medicine. Science and art converged in works like Elizabeth Blackwell’s A Curious Herbal, along with German naturalist Lorenz Oken’s seven-volume Allgemaine Naturgeschichte, consisting of more than 5,000 pages dedicated to classifying everything from beetles and fish to mushrooms and ferns.

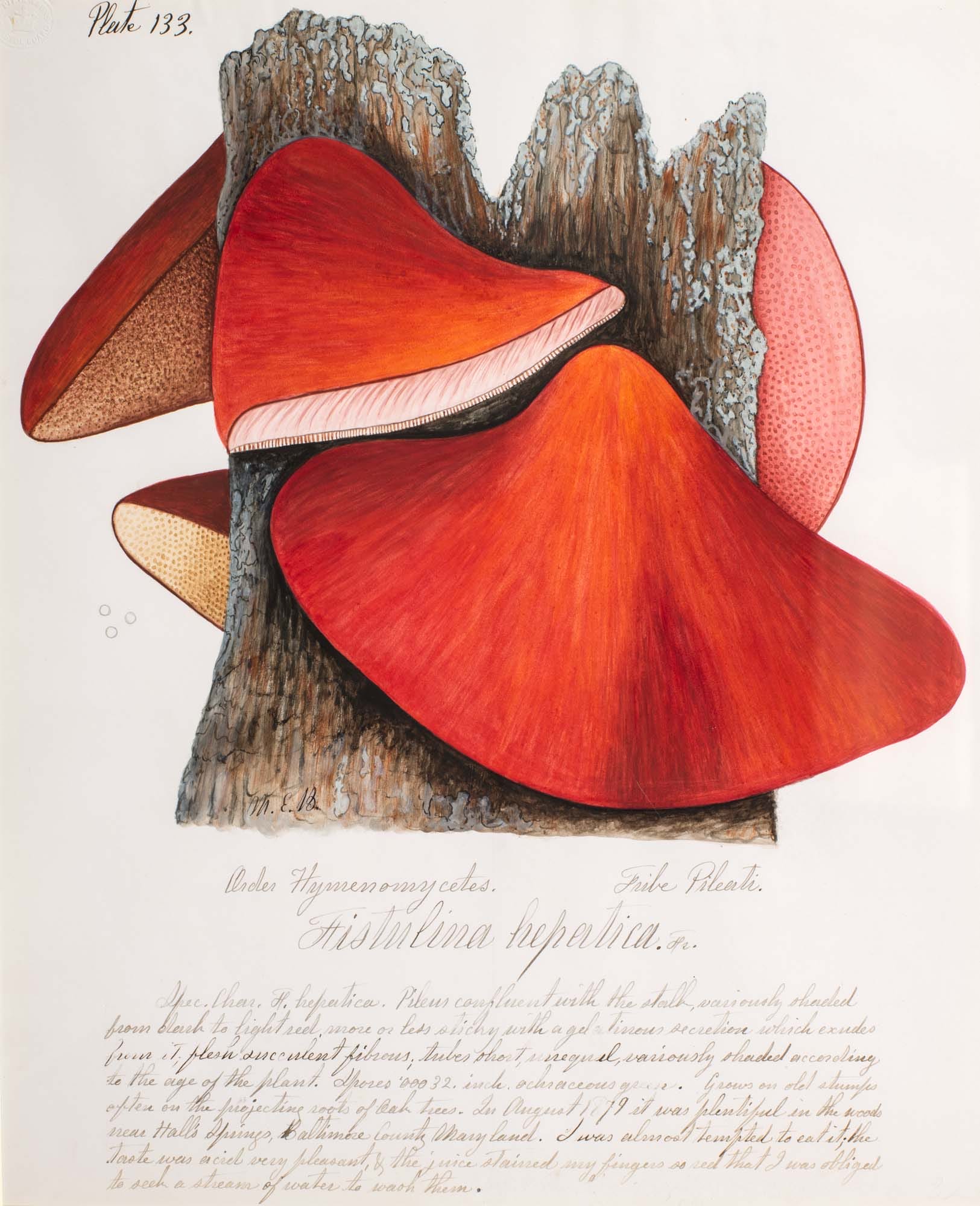

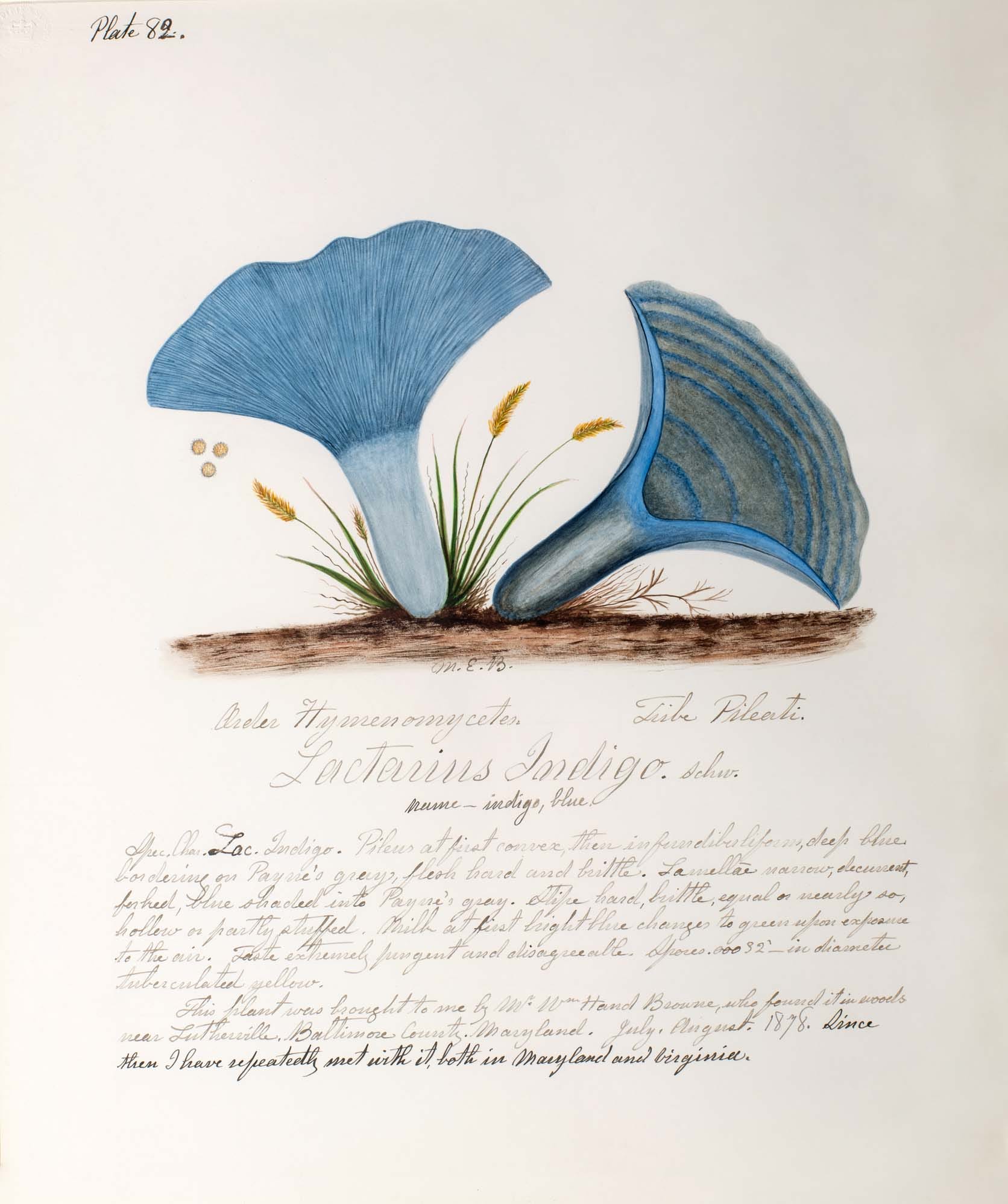

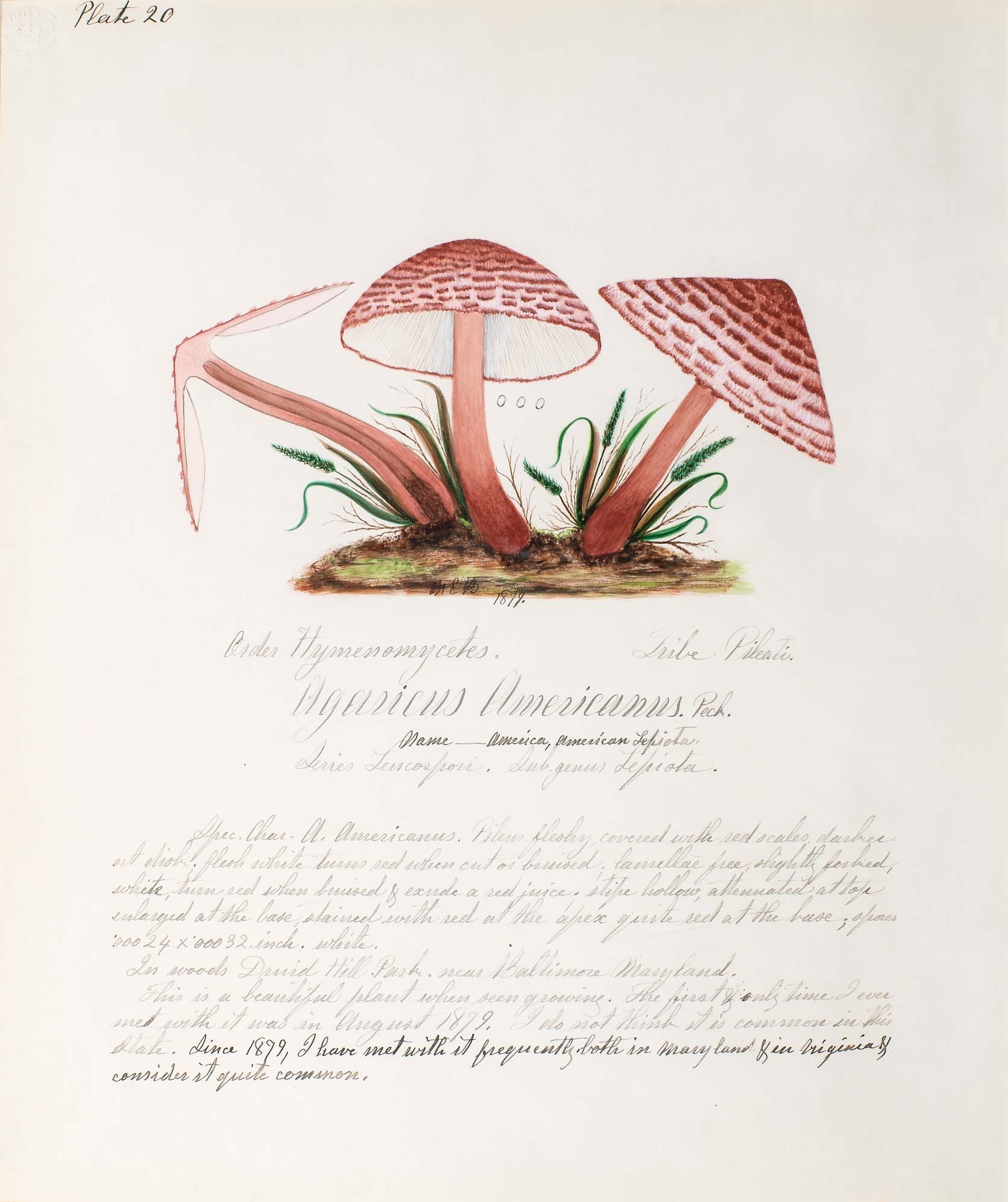

In the late 19th century in Maryland, Mary Elizabeth Banning (1822–1903) emerged as one of America’s first mycologists—and the first woman to describe a new fungus species to science. The self-taught artist and scientist is now the focus of a nature-centered exhibition at New York State Museum, Outcasts: Mary Banning’s World of Mushrooms. The show features 28 original watercolors and detailed records of various mushroom species from the unpublished manuscript of her book, The Fungi of Maryland. In fact, of the 175 species she documented, 23 of them were unknown to science at the time.

Banning’s manuscript is dedicated to Charles H. Peck, whose role as New York State Botanist—and an enthusiastic mycologist—at the NYSM formed the foundation of a 30-year correspondence with Banning. As a woman in an almost entirely male field, who also lacked formal biology degrees, Banning was largely ostracized from professional proceedings at the time, but her work did not go unrecognized. Peck published some of her findings in the Annual Report in 1871, and he kept her manuscript in a drawer at NYSM, where it remained for more than nine decades.

A handful of Banning and Peck’s letters are included in Outcasts, along with some of Peck’s lab equipment, mushroom specimens that Banning collected, and a dozen early 20th-century wax models of fungi from the NYSM Natural History Collection.

Along with Banning’s vibrant illustrations, the exhibition introduces visitors to the mycological universe, including prehistoric specimens like Prototaxites. A fossilized example of the ancient life form was found in Orange County, New York. Around 420 to 370 million years ago, these unique organisms would have towered over the landscape at up to 26 feet high.

Outcasts: Mary Banning’s World of Mushrooms continues through January 4 in Albany. Learn more and plan your visit on the museum’s website.

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $7 per month. The article ‘Outcasts’ Highlights the Scientific Contributions of Trailblazing Artist and Naturalist Mary Banning appeared first on Colossal.