Amarie Gipson On The Reading Room, Houston’s Black Art and Culture Library

One of Amarie Gipson’s many gifts is an unyielding desire to ask questions. Having worked at institutions like The Contemporary Austin, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Studio Museum in Harlem, Gipson has cultivated a practice of examining structures and pushing beyond their limitations. Her inquiries are incisive and rooted in a profound respect for people of all backgrounds, with a central goal of expanding art’s potential beyond museum walls.

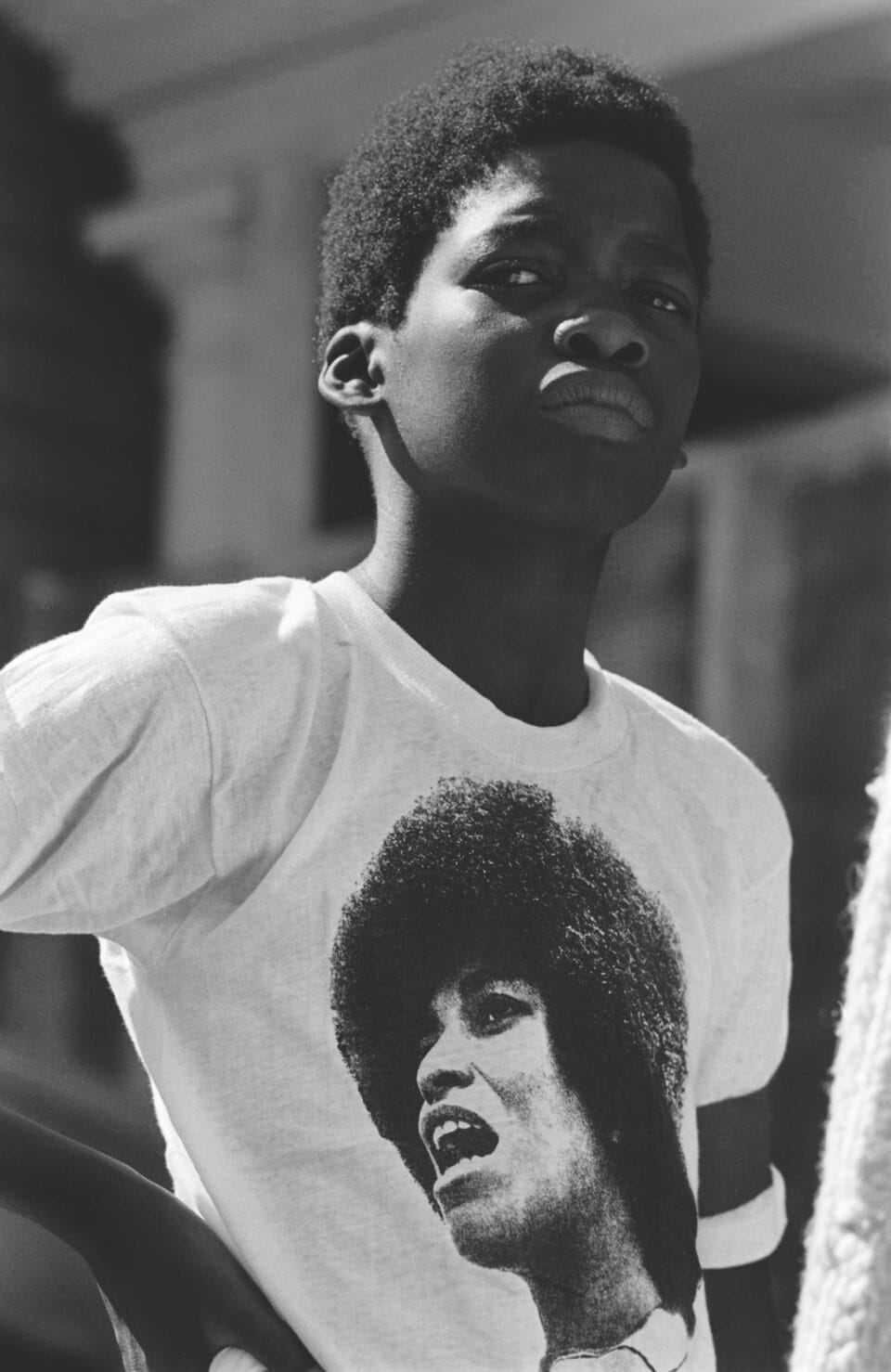

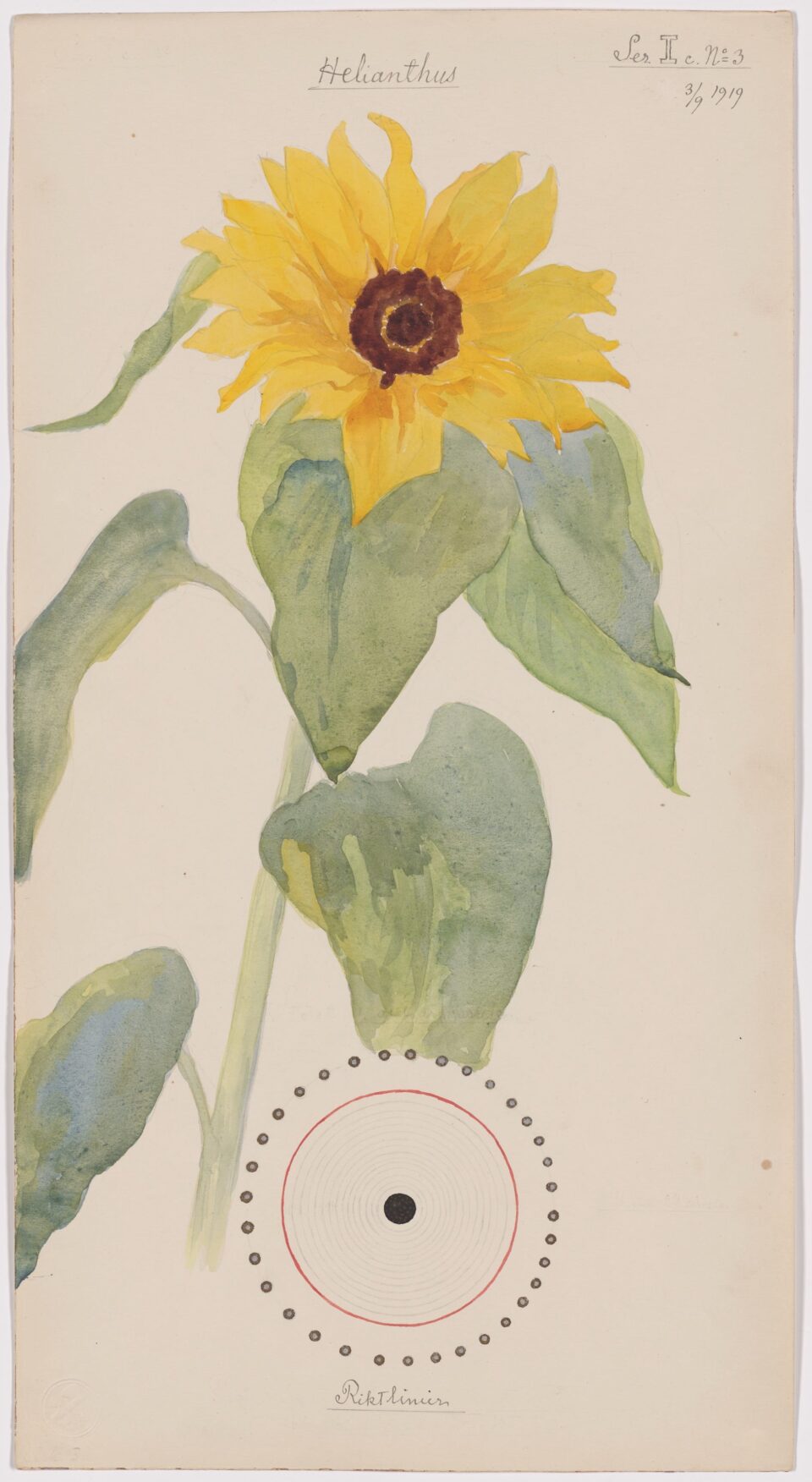

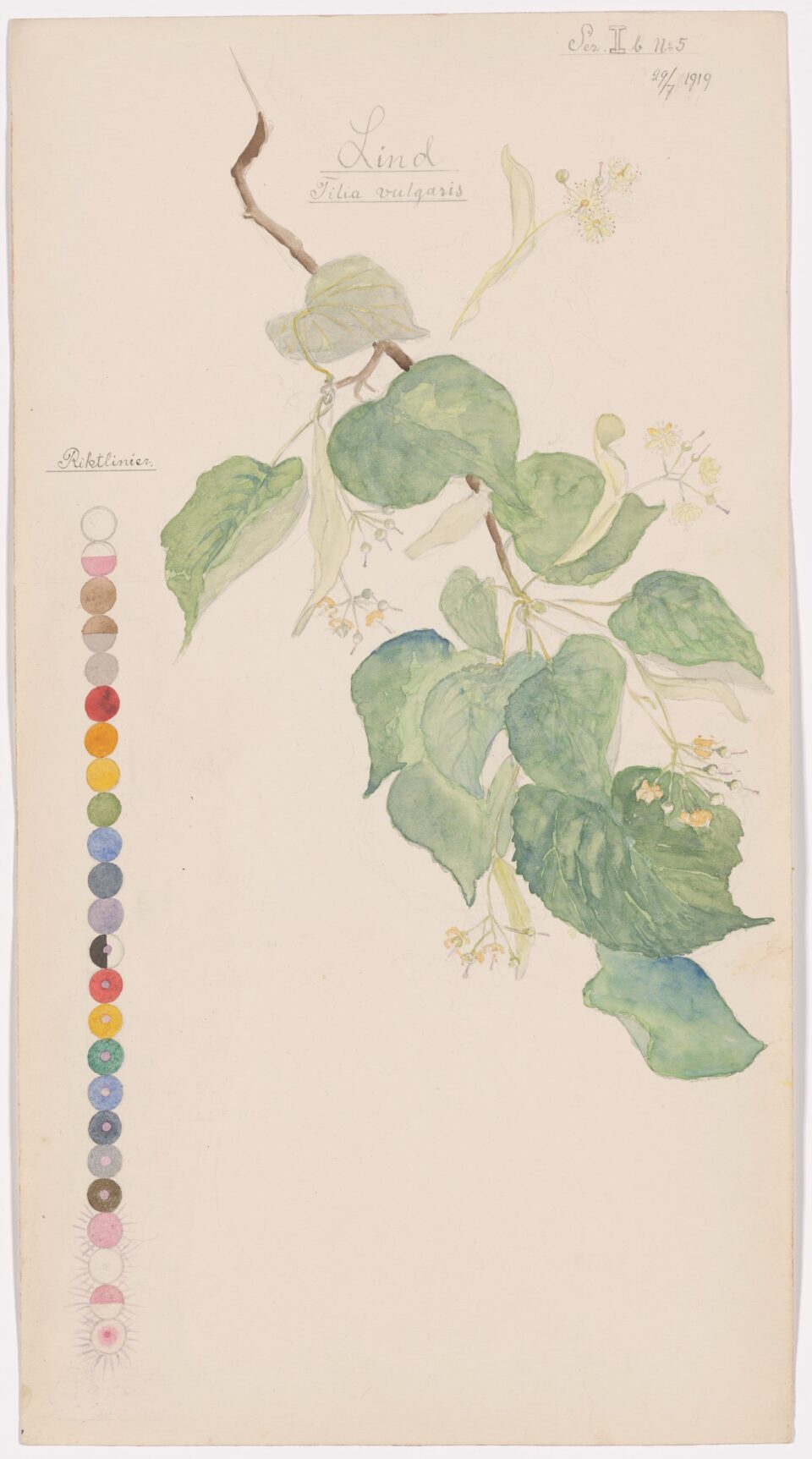

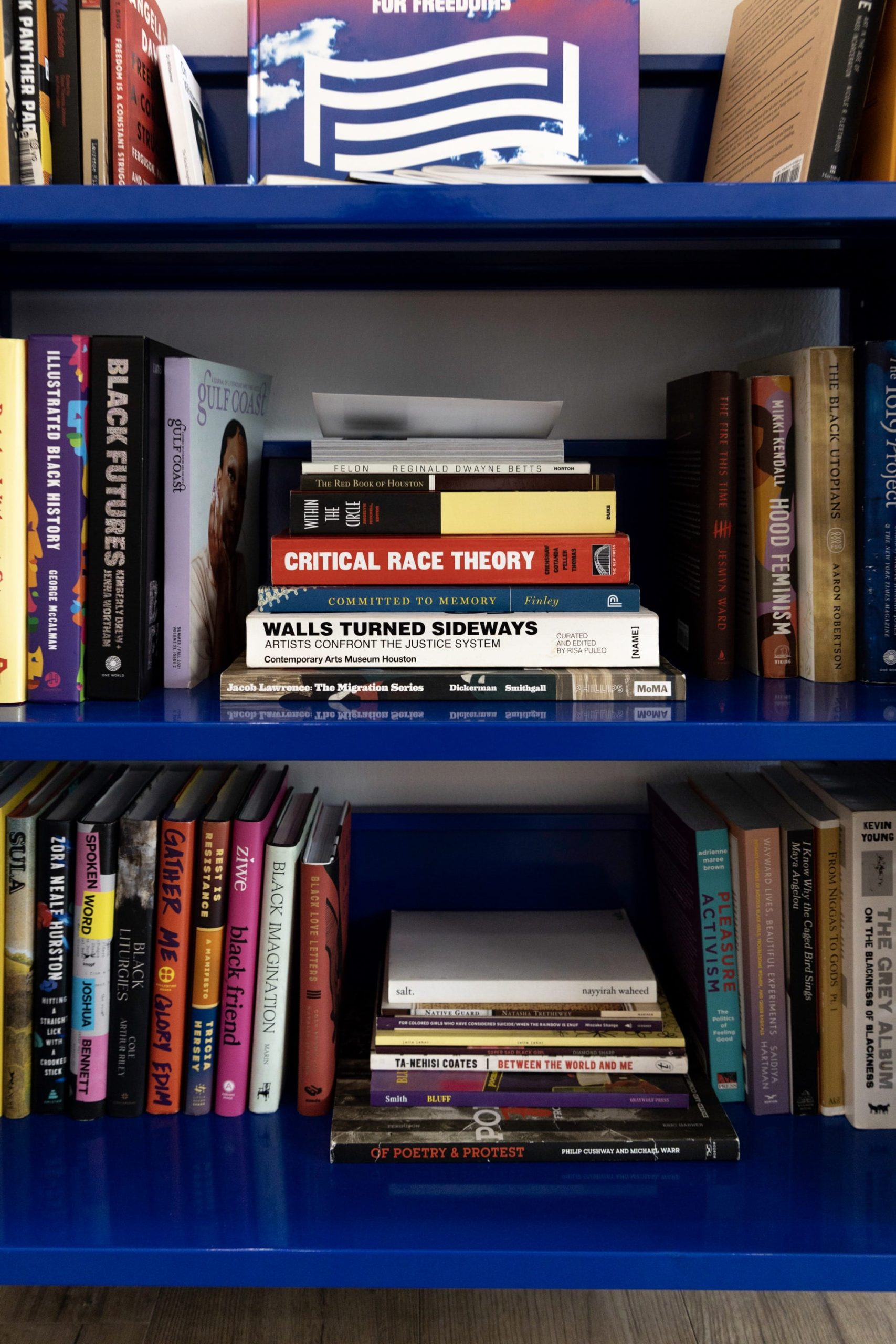

A true polymath, Gipson is a writer, curator, DJ, and founder of The Reading Room, an independent reference library with more than 700 books devoted to Black art, culture, politics, and history. Titles like the century-spanning African Artists sit alongside Toni Morrison’s novel Sula and Angela Davis’ provocative Freedom is a Constant Struggle, which connects oppression and state violence around the world. The simultaneous breadth of genres and the collection’s focus on Black life allow Gipson and other patrons to very literally exist alongside those who’ve inspired the library.

One afternoon in late April 2025, I spoke with Gipson via video about her love for the South, her commitment to meeting people where they’re at, and her hopes for The Reading Room.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Grace: I’d like to start at the beginning. Why start a project of this nature in Houston?

Amarie: I am a student of so many incredible Black women writers, artists, curators, thinkers, and theorists, and I really take seriously the advice that I’ve gotten through reading their work. If something doesn’t exist, you should start it. I’ve moved and migrated through these great United States for some time, and when I moved back to Houston seven and a half years ago, The Reading Room didn’t exist. I needed it to happen. I wanted to experience my books somewhere outside of my apartment, and I also wanted to create a destination for folks when they came to town, so that my friends know that they have a cool place to land. Those are the two main reasons: it didn’t exist, and I wanted somewhere to go.

Grace: There’s a thing that happens in Chicago all the time–I think it happens anywhere that is not New York or Los Angeles–and the ways artists think about their careers and what it takes to be successful. There’s often this perception that to reach a certain level, they need to go to one of those two cities. And I would imagine Houston has a similar feeling.

Amarie: Absolutely. I think it’s important that everyone leaves home at some point. But don’t leave because you don’t think that anything exists here. Leave because you want to see what else there is and bring it back. Come back home and create the things that you want to see here.

I don’t think I could have The Reading Room in New York. I don’t think I could have The Reading Room in Chicago. It’s not my home. I feel more empowered here. I feel safer to have created something like this, especially in a state that is so extremely suppressed, politically, socially. But culturally, we stand firm, especially in Houston. So, it felt natural.

Grace: What area of Houston are you currently in?

Amarie: The Reading Room is currently located in north downtown, right across the way from the University of Houston’s downtown campus. Downtown is not the most exciting place in the city, but it is a meeting point for all different types of cultures. The Reading Room lives inside a hybrid art studio called Sanman Studios. There are two units. They function as an event space and production studio. There’s an art gallery, an artist residency work space, and The Reading Room. This is Houston’s creative hotspot.

What more can we do to connect to the people? How can we bridge the gap between the folks who care about Black art and those who care about Black people and the things that affect us?

Amarie Gipson

Grace: I’m wondering how your institutional training has influenced The Reading Room. How have those experiences pushed you to make something that is decidedly not institutional?

Amarie: I was just thinking about this a week ago. I came into the curatorial field around 2016, and that was at the height of philanthropic institutions looking for ways to diversify. One of the solutions was to introduce younger, undergraduate-aged students from underrepresented communities to the field. I did the Mellon Undergraduate Curatorial Fellowship at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. I was a junior in college at the time, and this program really gave me a crash course on what museums are like; how the exhibitions are produced, where the art is stored, and how curators work with other departments. I spent two years at the MFAH in the Prints and Drawings department, and I was always looking for Black artists. I realized quickly that if no one’s here to advocate for this work to come out of storage, no one’s ever going to see it. I was trying to sift through the collection, find, locate, and make these works more visible.

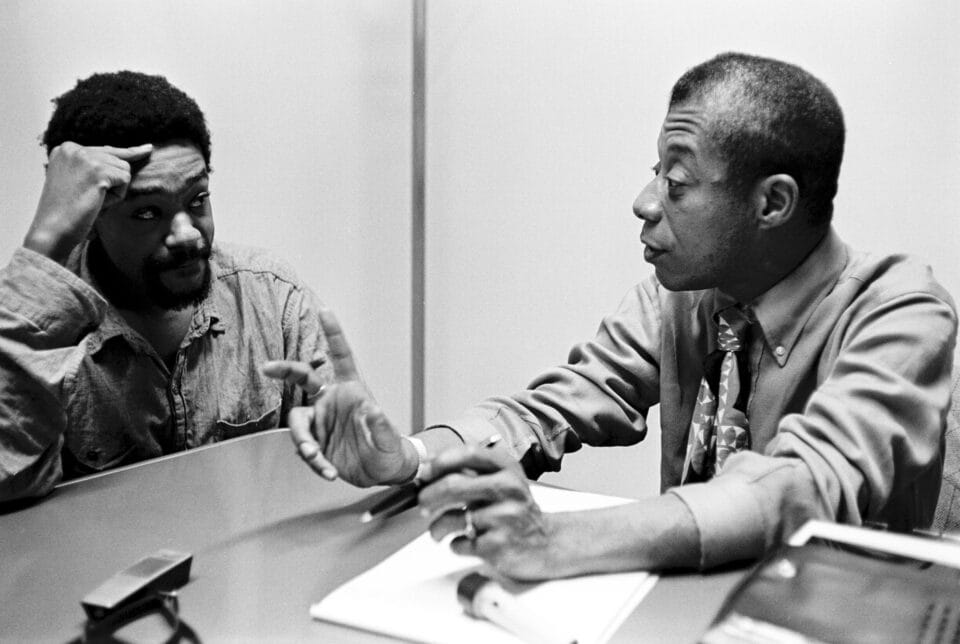

I also recognized early in my career that people are really important to me. I started asking questions: What are the functions and responsibilities of art institutions? What are we really supposed to be doing? I know what we have done, but what is the purpose? I eventually took those questions to Chicago and New York, and I moved around to different museums to try to find the answer.

A turning point was when I got hired at the Studio Museum in Harlem, which, for any young Black person in the art world, is the pinnacle. It’s the place. It’s where a lot of careers start. Many folks’ first job in the art world is at the Studio Museum, and they’re being shaped and molded to continue in the field. However, shortly after arriving, I realized the Studio Museum was not the place.

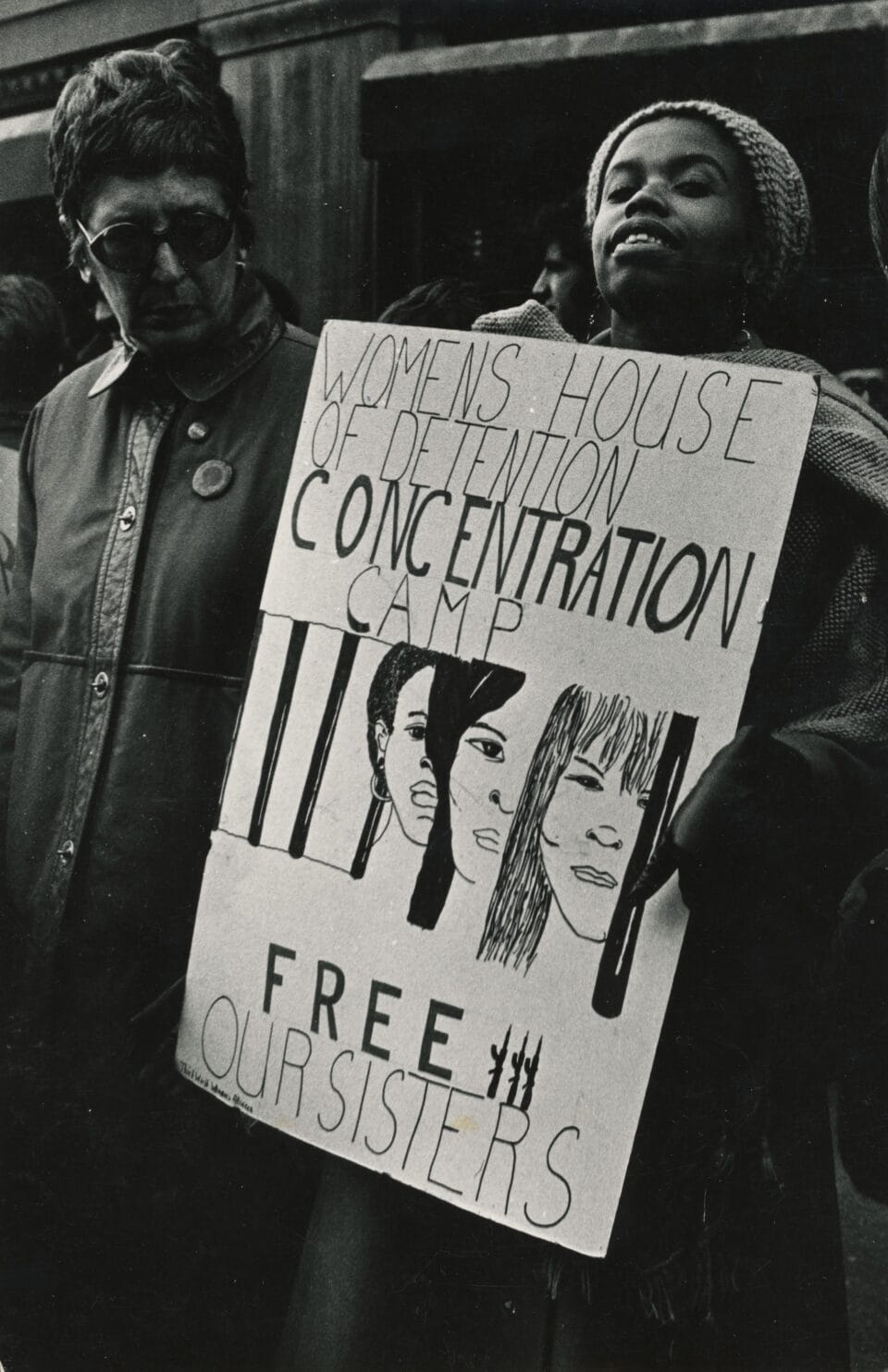

In 2020, I looked around at all the different institutions across New York sharing statements of solidarity and pledging institutional and systemic changes. I wanted the Studio Museum to do more than say, “We’ve been doing this. We’ve been committed.” Because what are we doing and does that commitment to care only benefit Black artists, or does it show up in our consideration for all Black people? There are real Black people who are being targeted and locked up for protesting the fact that police are murdering us. What more can we do to connect to the people? How can we bridge the gap between the folks who care about Black art and those who care about Black people and the things that affect us? What about the people working in and for the museum? What are we doing to support the struggle outside of working our lofty little museum jobs? The response that I got is that the institution is going to keep doing what it’s been doing. And that just wasn’t enough for me. I worked in my whole career to get there, but I realized that it was not the place I thought it was or hoped it could be.

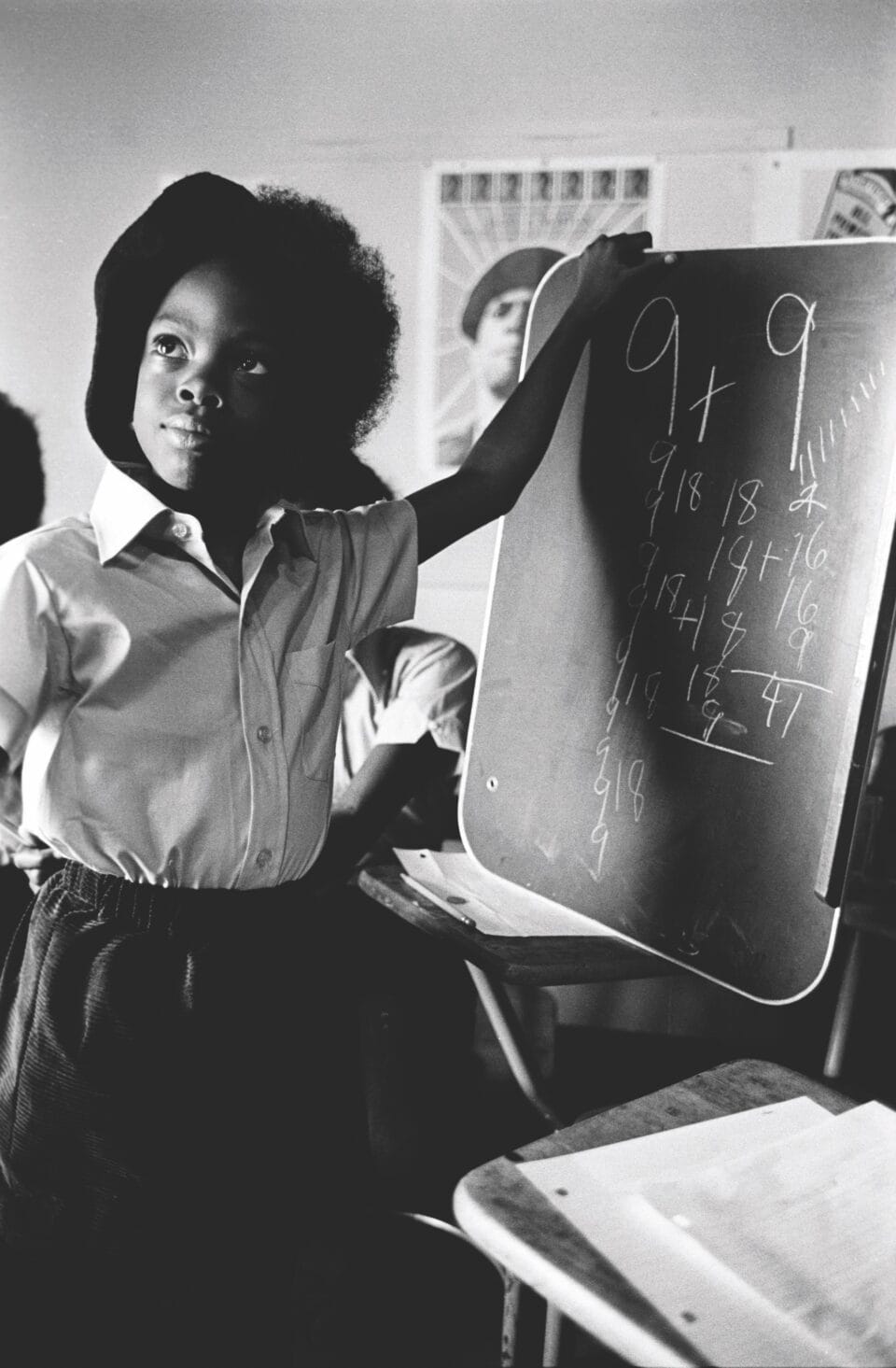

And so I left that job and found a way to connect my beliefs with my actions. I’ve taken all of the skills that I’ve learned—how to build relationships, how to listen, how to analyze and organize things, record keeping, data management, object management, storytelling—and do something totally different, something that prioritizes everyday Black people in a way that boosts our intellectual, cultural, and creative capacity. If it’s increased access to literature, if it’s increased access to culture, if it’s just a place that has air conditioning, a place where people can come and hang out, so be it. It’s making space for it all in a way that hopefully destroys the out-of-touch, elitist hierarchy that surrounds “the work.”

Grace: That’s one of the things that I think is so powerful about The Reading Room and the work that you’re doing. Art books are notoriously expensive, and other than sporadic free days, museums generally are not cheap either. You really do balance such a strong aesthetic perspective and a critical rigor typically associated with institutions with the accessibility of something like a public library meant for truly everyone. I wonder, on a tangible level, what goes into making a space like that?

If it’s increased access to literature, if it’s increased access to culture, if it’s just a place that has air conditioning, a place where people can come and hang out, so be it. It’s making space for it all in a way that hopefully destroys the out-of-touch, elitist hierarchy that surrounds “the work.”

Amarie Gipson

Amarie: I didn’t have a physical space when the idea first came to life. I started working on the concept in the summer of 2021. I passed by an old American Apparel storefront in this neighborhood in Houston called Montrose. I remember going to that American Apparel as a teenager. I never could afford anything, but I was always going in there to try stuff on. I looked inside, and I was like, what would I do if I had the space? At the time, I didn’t really know how anybody could afford anything outside of paying their rent. People who had small shops, coffee shops, small businesses, kitschy little stores, I was like, what do you need to do in order to make this happen? I eventually found my way to Sanman. I met Seth Rogers, the owner. I was working for a magazine, so I started asking him questions.

I was also DJing at the time. I had been DJing for four or five years prior to moving to Houston, but my DJ career blew up when I moved back because the culture here is so rich. Nightlife is a huge part of the city. I started saving my money from my day job, gigs, and partnerships. I would be at the events that I would play, and I’d be yelling to people over the speakers, “I’m building a library. I’m building a library!”

I lost my job at the magazine in the fall of 2022, and I had come upon enough money to focus fully on The Reading Room. I built the website to anchor the concept. I scanned the front and back covers of 325 of the books that were in the collection at the time. I built a strong relationship with Sanman and hosted a two-day, in-person experience after I launched the site. There were about 130 people who came that weekend just to hang out. Someone approached me and said, “I didn’t even know this many books on Black art existed.” That was the moment everything made sense, when I realized I’m on the right path.

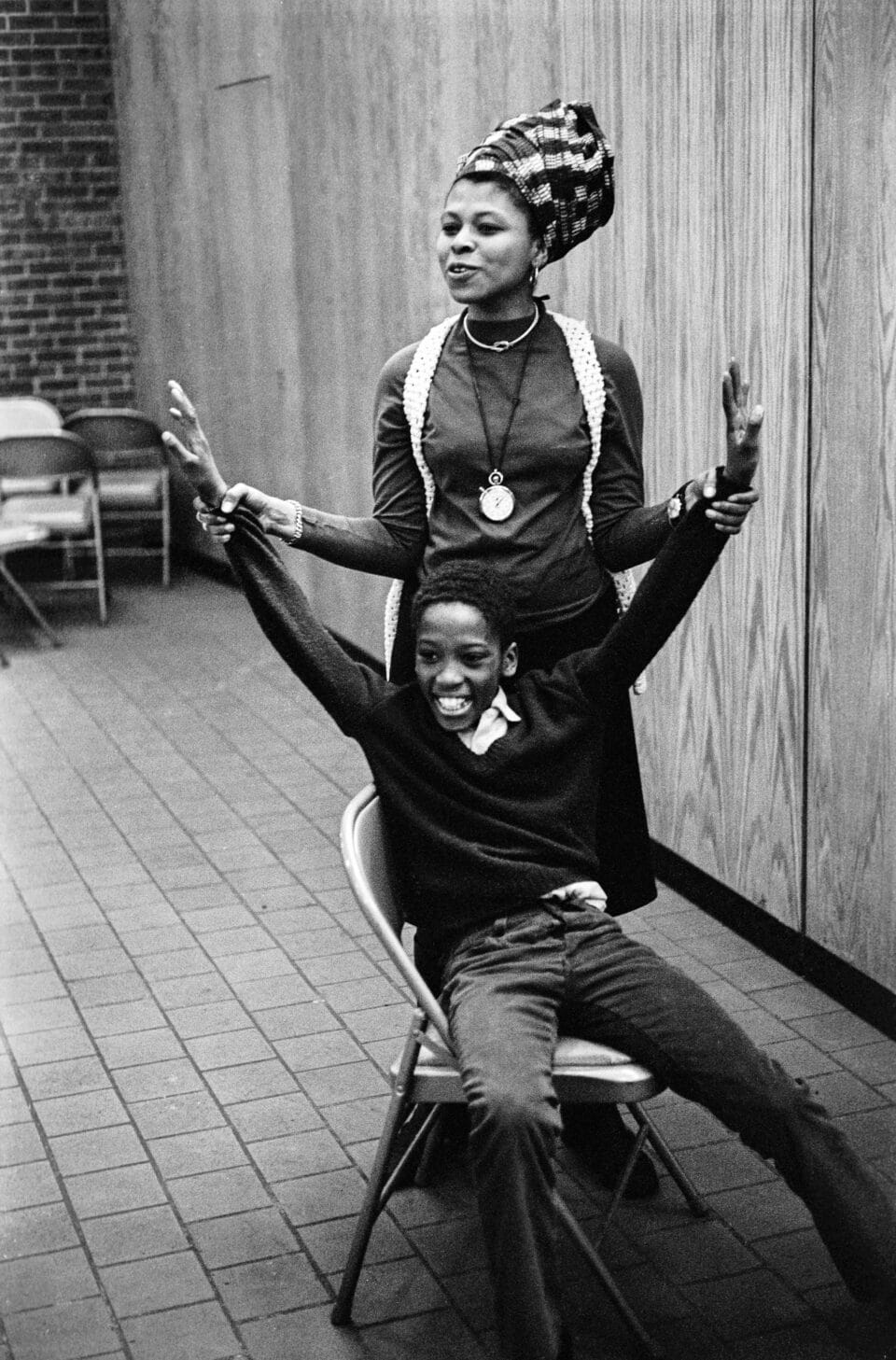

Because this is a reference library, where the collection doesn’t circulate, we’ve got to do programs. Every single program that we do is inspired by or connected to a book that’s in the collection. That’s bringing people in, and it’s leaving them with a reading list so that they can keep coming back. That’s been the formula so far. My ambition is to garner enough support and community response so that when I break out of a shared space, the traffic is steady and the impact deepens.

Grace: When we think about meeting people where they’re at, so much of it is about creating multiple entry points into the work that you’re doing. When someone comes in, what does that process look like? How do you engage with them?

Amarie: It depends. Most folks are just like, oh my god, I love this space. Some other folks will be like, I’m working on a project about Black hair. Do you have any books about hair? And I’ll go and pull books about hair. I’ll explain the relationships between the books on the main display and point out how I’ve selected and placed things, then give a crash course on where you can find what.

So even if they don’t know what they’re looking for, pointing them in a direction, they’ll be able to wayfind. It’s a destination for discovery. You come in, and you fall down a rabbit hole.

Grace: I think of curation primarily as a way of providing context. I’m wondering how the vastness of your collection—in that there’s history, politics, and culture, and you’re not focused on only having visual art or photography—manifests as part of your commitment to accessibility. What you’re doing in making these larger connections and providing context so that people don’t need to read an artwork or image through a traditional art historical, canonical perspective, but rather can approach it through music or politics or a cultural moment, feels like an accessibility move to me.

Amarie: You said it so beautifully. Seriously, that’s it. The books that people are familiar with are what’s going to draw them in, and then they’ll see that the bulk of the collection is about visual art. Hopefully, what they know is a gateway to what they don’t know and what I want to share. If you open up Arthur Jafa’s monograph, MAGNUMB, I want you to know Hortense Spillers and Saidiya Hartman. You gotta know all these people. Their books live here because they’re in conversation with one another. The artist’s monograph lives alongside the anthologies or the novels that inspired the creation of the work. The collection focuses heavily on visual art, just because that’s what I collected. I’m thinking about visual culture at large, but also history. How do we situate these objects within a larger continuum? We live within that continuum, so it’s important to see everything in concert with one another.

To your point about accessibility, it starts to tap into that more tangible effect, tangible impact, right? We can have conversations about politics in here, and it doesn’t necessarily have to be through the lens of an artist, but because the book lives in the collection, we can sit and talk about anything, right? We can talk about democracy or the lack thereof. We can talk about the American flag. We can talk about anything because there’s something here that’s going to help us situate it. We can listen to the music. There are so many intersections, and having collection categories that expand beyond art and design allows for that.

Grace: I was reading an older interview with Martine Syms recently about her publishing practice. She talked about publishing as a way to make ideas public—and then to use that to create a public around an idea because you have shared reference points. That feels very similar to what you’re doing. The Reading Room, by bringing people together and allowing these conversations, is actually creating this collective idea and an opportunity to have this shared way of thinking about something.

Amarie: For sure. I think about that a lot. Art books, not only because of the price, are largely inaccessible to the public, but are also inaccessible to artists who deserve them. You have to go a long way in your career before somebody feels like they care enough to make a book for you. You usually have to wait for a major retrospective or survey exhibition. Or if you’re really young and hot and you’ve got gallery representation, they might make you a book.

I’m also thinking about how The Reading Room can be a source, a bridge, or a doula that finds ways to amplify artists who are being overlooked or have been working for a really long time and still don’t have books, how their work can land in the hands of the public in a way that is accessible. I’m hoping to start a publishing branch of The Reading Room in the next couple of years. I’m going to start with zines this year and see what happens.

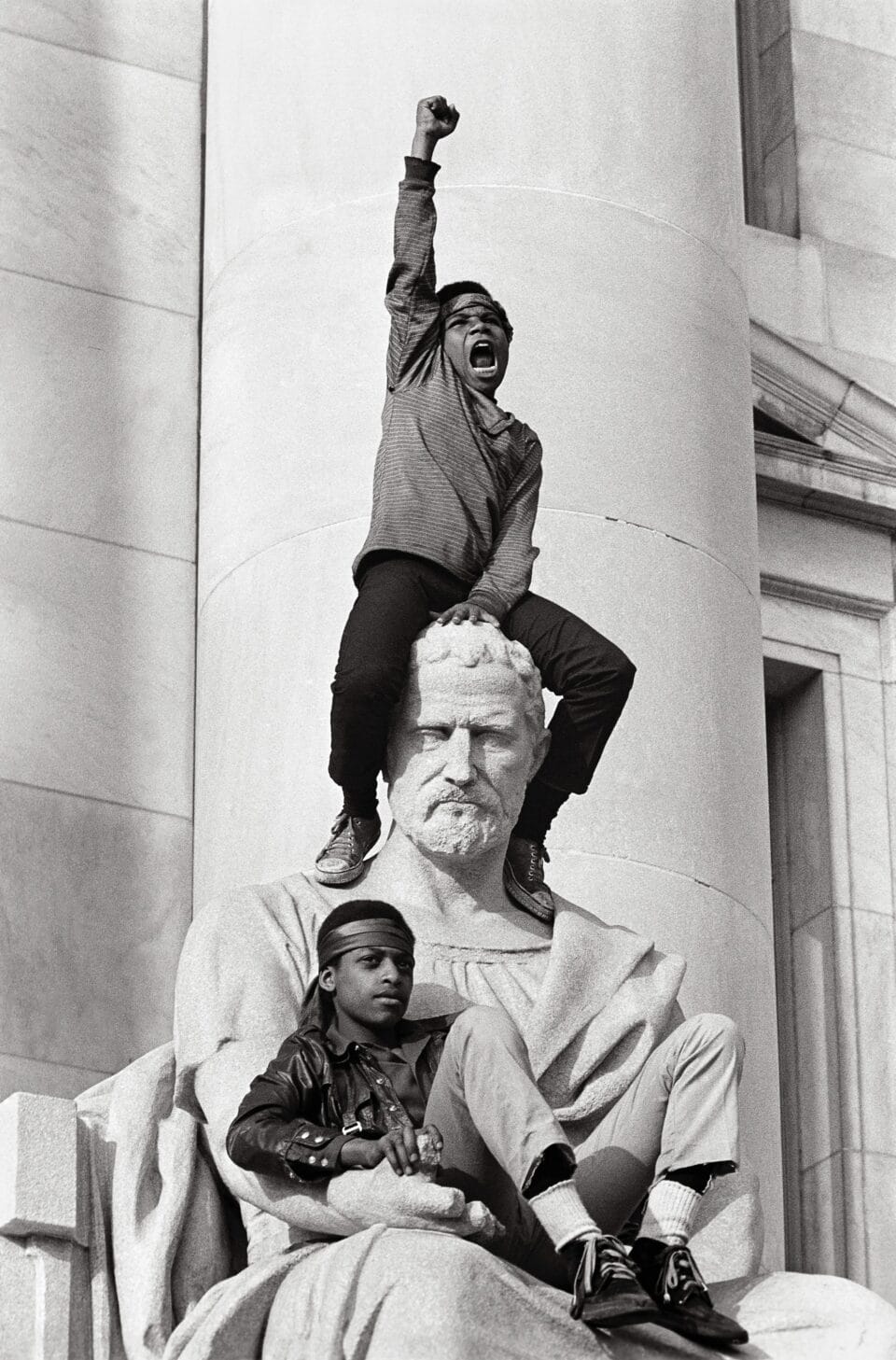

I’m also thinking about the legacy of independent Black publishers across history, coming out of different cities, and what it means right now in the age of misinformation, to create a platform for truth. Yeah, it will be making art books. But we’ll also be making political pamphlets, recirculating ideas from the past. How many people know what the Black Panther Party’s 10-point platform really was? What if we made posters? How can we apply those things today? I’m interested in all of that. I want to do every single thing that I couldn’t do in those museums, that’s too taboo or too controversial to do in a museum.

I feel way more present and clairvoyant than ever before. I realized that for the first year of running The Reading Room, I was like, I’m not reading enough. I was focused more on the structure of this thing, filling in gaps in the collection, all of that. Last summer, I made a summer reading list for myself, and I read ten books. It felt so good to just stop and read. I feel healthier, calmer, and stronger. I’ve been transformed. I want that feeling for everybody.

The Reading Room is open from 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. Wednesday to Sunday at 1109 Providence St., Houston. Explore the collection in the online archive, and follow the latest on Instagram.

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $7 per month. The article Amarie Gipson On The Reading Room, Houston’s Black Art and Culture Library appeared first on Colossal.